Devil at the Door: The Devil in Paradise Lost & Mike Carey’s Lucifer [3/3]

This segment within the series contains some spoilers for the Lucifer comic book series. You’ve been warned!

The first two parts of the article can be found here and here.

A Question of Medium

All creative work is up to interpretation, and it’s literary work that tends to dwell in this ambiguity even more than others. John Milton’s Paradise Lost is notoriously ambiguous to literary scholars, and the interference of his narrative figure makes it even more difficult to determine what he was trying to do with the figure of Satan within his work. Interestingly enough, Mike Carey’s Lucifer doesn’t have a lot of difficulty because it’s a comic book. The visual element of the medium lends a lot of power Carey’s vision of the Devil.

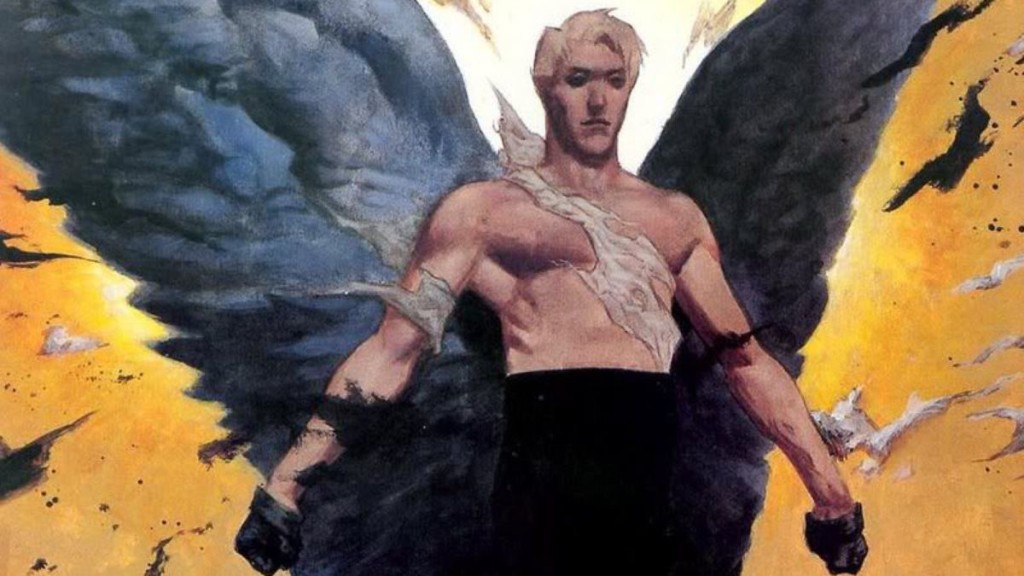

Although there is a textual narrator present in Lucifer, much more of the story is told through the dialogue of the characters and what the reader himself sees in the comic – and what any reader will see in the series is a blond, golden-eyed man who is as wicked and wickedly witty as he looks. Carey and the artists behind Lucifer present him as he is, and make no value judgments on his actions whatsoever. Furthermore, they don’t bother to hide the fact that he was, once upon a time, an angel. They also let the monstrosity of his actions speak for themselves rather than give him a pitchfork, or a tail, or any other hideous addition to drive home some point about him being “evil”.

Part of the Devil’s power as an archetype is defined by those who read him and adhere to the symbolism behind his character. With this in mind, one could say that Carey’s decision to write Lucifer as a comic, blending powerful imagery with equally powerful words, enables him to reach out to a more general audience, the very audience that decides upon which lens to use in interpreting the idea of the Devil and of evil. Because Carey structured the character of Lucifer Morningstar as a protagonist, his readers find themselves encountered with an entirely new version of a devil that they are supposed to be intimately familiar with. Hence, the visual element of the comic becomes indispensable to the presentation of Lucifer as a whole: a narrative account communicated solely through text would rely too much on the propensity of words. The usage, meaning and interpretation of words differ subtly but significantly on an individual basis: these differences might end up detracting from the force of the reimagining. Visual images provide a much more immediate effect, and have less difficulty in invoking emotion or provoking a reaction from the reader.

The Disobedient Son: Mike Carey’s Lucifer

The most crucial difference one must note between John Milton’s Satan and Mike Carey’s Lucifer is that where the Satan of Paradise Lost is just a rebellious angel, Carey’s Lucifer is positioned alongside the archangel Michael as “a Son of Yahweh”. Carey achieved this by making some modifications to the Judeo-Christian creation and combat myths. First, the creation myth was modified to show how God first created Michael and Lucifer, and then created the universe using them as tools (Lucifer, Issues 25-26 & 75). Second, Lucifer’s rebellion was sparked not by jealousy over Adam and Eve, but because of his conversations with Lilith about autonomy and his desire to break away from the Father — he then waited for the opportunity to declare rebellion, which presented itself in the crisis of the Lilim (Lucifer, Lilith). Finally, there is a deliberate absence of the figure of Jesus Christ as a character in Lucifer: the figure of God himself calls Lucifer and Michael his sons. Carey even goes so far as to create new “trinities”: the first is between God the Father, Lucifer and Michael, the first of his creations. The second is between Lucifer, Michael and Elaine Belloc, Michael’s daughter.

Positioning Lucifer in this fashion emphasizes his status as part of the Divine Family, and while it may not make him equal to God the Father in power, it does make him appear to be more of a direct binary opposite to God than Satan was in Paradise Lost. The comic then involves itself in a very different direction from the traditional iconography of the Devil — where most texts depict a descent or stagnation, Carey’s Lucifer depicts a constant ascent in the Devil figure’s stature.

We have described how the iconography of the Devil has been a transition from the Devil as monster to the Devil as ‘human’. In Lucifer, Carey provides the next natural step in the process: the portrayal of the Devil as a comic, ‘elevated’ being. The visual portrayal of his character in the comic book shifted in order to match the change. Where in the first forty issues, Lucifer was a blonde, blue-eyed human man, the later issues show the deepening gold in his hair, the change of his eyes to gold, the re-instatement of his wings and the return — and increase — in his power as the Lightbringer.

Paradise Lost details the ‘downfall’ and reduction of Satan; Lucifer’s textual and visual narrative tracks Lucifer’s revival as an angel, and then watches as he catapults himself into godhood. Lucifer does have more than a few steep downfalls, but they are underscored by even steeper ascensions. Lucifer, in some ways, is even rewarded for never flinching from his principles: he survives in the end, and ultimately manages to leave Creation. He is even given the chance to speak at length with God once again in the final issue of the comic: his father appears to acknowledge Lucifer’s growth, and asks if they may share experiences. Lucifer rejects him, thus reasserting his personal autonomy.

Beyond his positioning as the protagonist and binary opposite to the antagonist in God the Father, Carey’s Lucifer seems to be a more “mature” character over Milton’s Satan. While they are both embodiments of pride, structuring their actions around their love of self, Lucifer does not display the same moments of self-doubt as Satan does: he is also more fully aware of God’s omnipotence, and both remarks upon his father’s nature and structures his actions within this consideration. Of course, while his rebellion is what defines him, Lucifer stresses that he acts primarily to please himself rather than to differentiate himself from the father. Furthermore, all of Lucifer’s actions are centered around furthering himself, or protecting himself and what he considers his own — what happens to any other party is of little concern to him. Overall, the evil of Lucifer’s character is unquestionable by moral standards, but it is ultimately secondary to his principle of self and willpower. “Lucifer’s quest for autonomy,” Carey himself says, “is his driving motivation and the very definition of his nature”. He was created, in the words of God the Father in the comic, to embody the strength of will. Satan, on the other hand, does not succeed in differentiating himself from his creator: he remains entangled in God’s plan, and his lack of confidence is what ultimately destroys his character.

Because Lucifer is the protagonist, he is thus ‘redeemed’ for achieving the principle of self: there are times when his actions have dire consequences, but overall everything comes full circle in the narrative. Satan was not given this liberty, as Milton intended Paradise Lost to be instructional with regard to the nature of evil. Whereas Satan is incapable of changing himself mostly because of the circumstances, however, Lucifer is incapable of change as a matter of principle, for changing would be denying his essential nature. Lucifer, then, is not necessarily made better by his experiences, but he is certainly not degraded, nor is he a figure to be pitied or reviled.

Another important difference to note is the fact that Lucifer is forwarded primarily as a work of fiction. Carey’s blending of many other religious texts and liberal use of world folklore emphasize this fact, as the presence of other god figures and the reduction, the absence or complete remaking of particularly important Christian symbols undermines the Judeo-Christian slate of the comic. Furthermore, Lucifer is not about the human concern for salvation, but the human dialectic of freedom and control within the structure of the family. A cosmic battle does take place (and inevitably so, given the characters), but the real focus of the comic is the relationship between a father and his quarrelsome offspring.

Portraying the figure of the Devil in this light lends a peculiar element to Lucifer that would not have been made possible if the Devil figure therein remained the traditional Judeo-Christian Adversary, antagonizing God simply because he is evil. We see, in a rare moment within literary history, that the Devil has finally been treated as a literary character with his own unique personality, memorable traits and convincing goals and motives for his actions.

Conclusion

The Devil, like any symbol, is meant to change with the times in order to suit particular human needs, or represent particular ideas, and the main idea that has always dominated the figure of the Devil is the prevalent belief that he is the personification of evil. Post-modernity and the rampant urbanization of the 21st Century, however, have caused the figure of the Devil to decline in prominence. The world at present is understood to be complex, contradictory and riddled with ambiguities. In this light, the “simplicity” of the Devil — that is, someone who is totally and purely evil — seems base and immature. He was something that could only stay within the realm of fiction, and even that made him seem like an unwieldy character because of his one-sided nature.

Mike Carey’s Lucifer has successfully resurrected the idea of the Devil by emphasizing his nature as a character, outside of our own personal biases and beliefs. He is unique in his portrayal of the Devil as a protagonist, and by doing so he has given the character of the Devil newfound depth and complexity. His Lucifer Morningstar could not possibly care what befalls humanity, or how best to turn human beings away from God: his only concern is himself, and his ultimate goal is to establish his independence from his father. Human beings are entirely free to occupy themselves in his opinion, and what they do with their time does not matter to him. His motivations, then, are self-driven, and not entirely dependent upon the figure of God. Furthermore, Lucifer Morningstar is dynamic: although there are aspects of his character that do not change, his character does not emerge from the narrative of Lucifer without learning or gaining anything new.

Milton may have taken the first step towards differentiating the idea of the Devil from the idea of evil, but it was Carey who made the transition. The arrival of his Lucifer Morningstar is an impressive reemergence of the literary Devil to both readers and critics alike. Carey and his work have forwarded the idea of the Devil as a “floating signifier”: a symbol free from its traditional meanings, and different in its current representation from its original origin. Once a symbol or metaphor has become a floating signifier, it is capable of evolving further into something more universal and ultimately longer lasting in literature: it also indicates a change in human thought, and change is always worth studying. A floating signifier has the freedom to change its meaning to properly reflect the sentiments of the times, and even a symbol as culturally complex as the Devil can be and deserves to be treated in this fashion.

REFERENCES

Bal, Nieke. Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative [2nd Edition]. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Carey, Mike. Lucifer. New York: DC Comics, 1999-2006.

Forsyth, Neil. The Satanic Epic. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Milton, John. Paradise Lost. London: Penguin Books, 2000.

Pagels, Elaine. The Origin of Satan. New York: Random House Incorporated, 1996.

Russell, Jeffrey Burton. Satan: The Early Christian Tradition. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1987.

Russell, Jeffrey Burton. Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1986.

Russell, Jeffrey Burton. Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1986.

Sanford, Peter. The Devil: A Biography. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1996.

Zipes, Jack. “The Contamination of the Fairy Tale”. Sticks and Stones: The Troublesome Success of Children’s Literature from Slovenly Peter to Harry Potter. New York and London: Routledge, 2002.

The SF Site. “A Conversation With Mike Carey”. The SF Site. <http://www.sfsite.com/10b/mc186.htm>

Comic Book Resources. “Hell Frozen Over: Mike Carey Talks About Lucifer’s Final Year”. Comic Book Resources. <http://www.comicbookresources.com/news/newsitem.cgi?id=5783>

![Devil at the Door: The Devil in Paradise Lost & Mike Carey’s Lucifer [3/3] Devil at the Door: The Devil in Paradise Lost & Mike Carey’s Lucifer [3/3]](https://i0.wp.com/whatsageek.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/luciferfeatured2.jpg?resize=782%2C440&ssl=1)