Devil at the Door: The Devil in Paradise Lost & Mike Carey’s Lucifer [1/3]

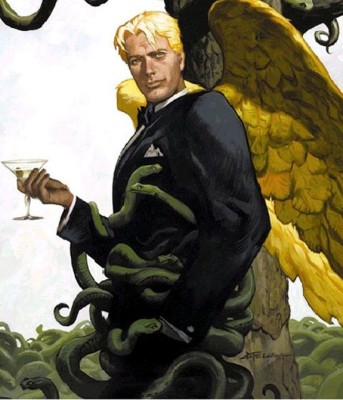

The up and coming train wreck of an adaptation of Mike Carey’s Lucifer for the small screen and the reboot they’ll be putting into print in December awakened two things in me: massive feelings of table-flipping rage (“BUT WHY THE FUCK IS IT A COP DRAMA?!?!?!”) and strong need to revisit my undergraduate thesis for English Literature. It was titled “Devil at the Door”, and was a comparative study of the figure of Satan in Carey’s comic book series and John Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost.

In honor of the memory of what Lucifer ought to be and in the spirit of further legitimizing Comic Book Studies as a discipline that we can all ride on, I’ve decided to publish a series of articles that cover the gist of my thesis. The point that I’m trying to drive home here is that the character of Satan in Paradise Lost and the character of Lucifer in Lucifer are two of the only works in literature that treat the figure of the Devil as a protagonist of his own story and not simply the foil of the so-called “Ultimate Good”, which pretty much explains why anyone whose read either of these works think that they’re amazing. This discussion’s going to be broken down into three articles, posted on this site every week until it’s finished.

Something that I’ll have to emphasize now is that the scope of my thesis was meant to cover the Devil as a literary figure. I didn’t really cover the way he’s portrayed in movies, cartoons, and television series for the purpose of comparison between the two texts in question. Granted, I do feel that a lot of the points that I made my discussion still apply to images of the Devil in other mediums.

A quick, final note on the format of all of these articles: I’ve decided to revert from our house style down at WAG to using the MLA citation style instead (don’t you college kids get any heart attacks over it now), and I will be posting a full list of my references in the final article. Furthermore, if any of you guys want to see the actual thesis instead of reading the condensed, geeked up versions that you’ll read here, feel free to contact me.

Let’s kick this off with an Ideology of the Devil

Satan, Adversary, Lucifer, Mephistopheles, the Prince of Darkness: these names are just five of the many that we’ve given to the Devil. While the Judeo-Christian God is the almighty Creator of the universe, the Devil traditionally serves as his quarrelsome and imperfect shadow, rebelling against God by undermining His creation. As such, he’s always served as a name and face for our idea of evil.

Now the question of evil has always been one of the largest – if not THE largest – challenges to human thought, especially for people coming from Judeo-Christian religious traditions. Judaism and Christianity believe in a single God, a mighty omni-everything being that created the universe. Because this God is understood to be inherently good, it’s assumed that everything that he creates is also good – but where does that leave the existence of what we view as “evil”? To justify all of this, we created the idea of the Devil. He is God’s cosmic rival, the guy who disrupts The Plan™ just because he can.

Since the idea of the Devil is rooted in Judaism, let’s take a look at their history. Anyone who’s read the Bible will know that Jewish history is one of tribal conflict, with people of the same race waging war and committing atrocities of great magnitude upon each other. In her book The Origin of Satan, Elaine Pagels describes how this background was integral in the development of the Judeo-Christian Devil. Early Jewish thinkers used the metaphor of cosmic battle in order to interpret human relationships: the Jewish people, both individually and collectively, characterized themselves as embodiments of transcendent forces. This, in turn, allowed them to vindicate themselves while vilifying — or shall we say, demonizing — their enemies (15). Hence, the Jews saw themselves as “the people of God” and those who stood against them as “agents of Satan”. Furthermore, because Satan had once been a part of God’s Host, it became easy for them to justify how they could come in conflict with their own race. If God’s own angel could betray Him, then it only followed that one’s own friends could betray their people.

We can take two points regarding the Devil figure’s function from this discussion. On one hand, the Devil is the eternal scapegoat that singularly explains the existence of evil and suffering. On the other hand, the Devil is the intimate enemy, a dangerous figure who rebelled against God and works to spite Him. Combining these ideas in different ways has produced a variety of different Devil figures throughout history.

From Monster to Man: A Brief Study of the Evolution of the Devil Figure

The earlier part of this article talked about how Jewish thinkers made use of the Devil figure, so let’s take a look at how other philosophers and religious dealt with him in the centuries to come.

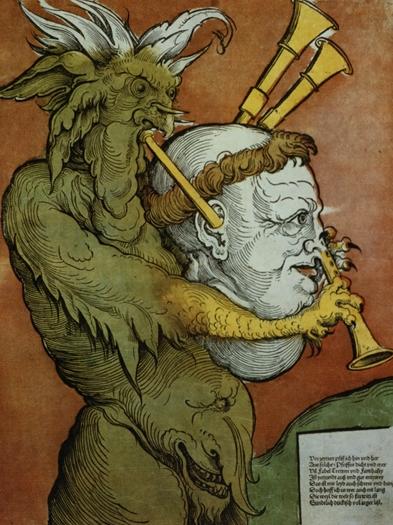

Christian philosophers in the Medieval Ages perpetuated the portrayal of the Devil as a monster for different reasons. Medieval Christian philosophy puts a great deal of emphasis upon the transforming and corrupting power of evil: doing evil tarnishes the soul, and the corruption of the soul leads to the inevitable corruption of the body. As such, one can literally become a monster if one commits evil acts constantly. As Satan is the embodiment of evil, it was necessary to portray him as a monster in order to emphasize his fallen state. Because he rebelled against God and works against God’s plan, Satan is a fearsome and ugly creature deformed by the blackness of his deeds.

A more “human-like” Devil occurred in tandem with the Protestant Reformation. The splintering of the Catholic Church kind of reflects the conflict between the Jewish tribes, but the fact that Protestants still believed in the same God and shared many of their religious customs made it difficult for their Catholic brethren to view them as monsters. Furthermore, the Church itself was responsible of committing unspeakable atrocities upon so-called “heretics”, yet they wore very human faces. The Reformation, then, seemed to espouse a new understanding of evil: that it was subtler, deceptive, and infinitely more dangerous because it resided in the familiar. Protestant writers, in tune with this new theme, refrained from describing the figure of the Devil as a monster, and focused instead upon describing the Devil as the Prince of Lies, capable of changing his form or being a malignant invisible presence in order to better deceive the children of God. Artists, though…

Anyway. Protestant thinking also questioned the nature of the Devil’s relationship with God because they took the idea of God’s omnipotence very seriously. According to Luther, for example, God is absolutely free to make Creation as he chooses, and Creation is completely under His control. Therefore, evil – and, by extension, the Devil – was all a part of God’s plan. God, then, “hides under the mask of the Devil”: and His will is present in everything, and His presence is what turns all evil to “ultimate good” (Russell 37). This reduction of the Devil figure is reflected in the literature of the time, which consistently relegated the Devil to a secondary role in both religious discourses and fictional works.

The fate of the Devil figure was later sealed with the rise of Rationalism and the Industrial Revolution. The newfound emphasis on science and scientific thought caused people to study the Devil under a more critical light, and more people began to doubt his existence. Belief in the Devil soon became unfashionable, and even the Church avoided referring to the Devil as much as possible. While it was generally easy for the majority to dismiss the Devil’s existence, however, it was harder to stop using the Devil as a metaphor for evil.

For some, the Devil continued to play his traditional role as Satan, the Adversary — for others, the Devil was a figure of irony or satire to mock Christianity or parody human folly. Some used the Devil as a symbol for human evil and corruption; others chose to appropriate him for their own purposes, championing the Devil as a symbol of rebellion against corrupt authority (Russell 156). What remained consistent in all of these portrayals are the authors’ attempts at humanizing the Devil — a necessary move, given the fact that the Devil was now a fictional character and every character needs a plausible motive. Attempting to show evil not in the monstrous but in the familiar also seemed like a more logical way of describing the nature of evil, and this reflected upon how the Devil was portrayed.

The second article in this series is going to talk about the Devil figure as a character in a narrative, and look into the way John Milton and Mike Carey did their thing.

![Devil at the Door: The Devil in Paradise Lost & Mike Carey’s Lucifer [1/3] Devil at the Door: The Devil in Paradise Lost & Mike Carey’s Lucifer [1/3]](https://i0.wp.com/whatsageek.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Lucifer_Comic.jpg?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)

![WTF Wattpad: ‘Claimed by my Bully’ [1/4] WTF Wattpad: ‘Claimed by my Bully’ [1/4]](https://i0.wp.com/whatsageek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/WTF-Wattpad.jpg?resize=390%2C205&ssl=1)