‘The Hunger Games’ – Spectacle, Panopticon & a Culture of Paranoia [2/3]

Here’s the second in a series of posts on The Hunger Games trilogy by Suzanne Collins. You can find the first post over here.

Please note that all of the articles collected under this series will contain spoilers for The Hunger Games trilogy. You’ve been warned!

The first post of this series served as a bit of an introduction to The Hunger Games. We emphasized how the trilogy was young adult fiction published during an intriguing in world history: the 9/11 tragedy, and the throes of the war on terror. We took a look at the systems of discipline and control employed by the fictional government of Panem. We also discussed the Hunger Games themselves, and how both the citizens of the Capital and the people from the Districts function in a world where censorship and propaganda is key.

This second post is going to discuss The Hunger Games in relation to the concept of the Panopticon.

A QUICK AND DIRTY DISCUSSION OF THE PANOPTICON

The discussion below is, by no means, exhaustive. Please check references like this one, beyond the original text on the Panopticon, if you want to learn more.

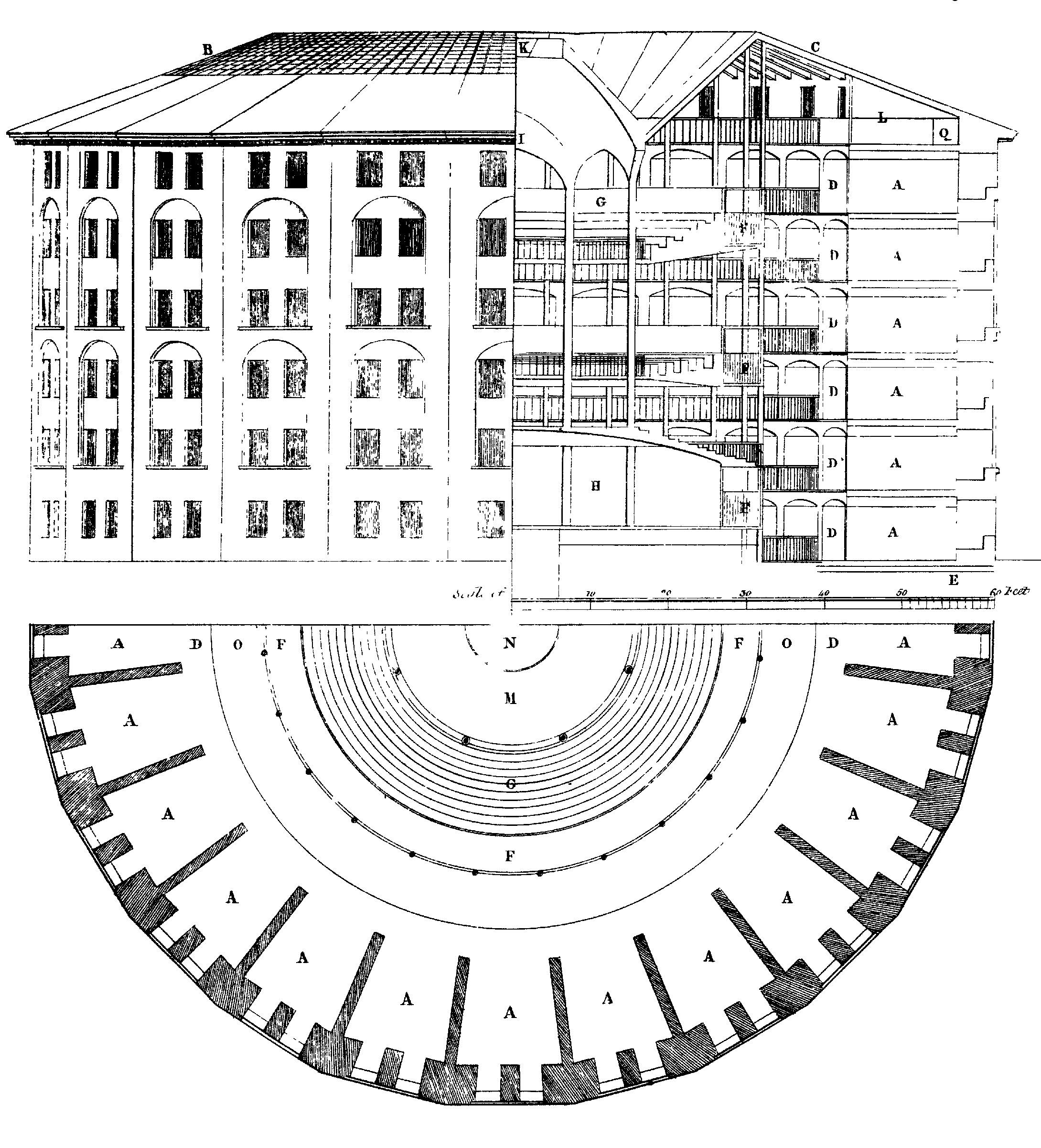

The Panopticon is “a type of institutional building” designed by English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham. It’s basically a prison tower that allowed prison guards to monitor large numbers of inmates effectively by taking advantage of their uncertainty and fear. We quote:

Although it is physically impossible for the single watchman to observe all cells at once, the fact that the inmates cannot know when they are being watched means that all inmates must act as though they are watched at all times, effectively controlling their own behaviour constantly.

Michel Foucault built on this by doing an analysis on two things: the measures of control taken against the bubonic plague during the 17th Century, and the structure of the guard tower in prisons. According to him, two forms of control are involved in the Panopticon: exclusion and disciplinary partitioning. Lepers were marked as “different” and separated – excluded – from the rest of “healthy” society, as were plague victims. Along that vein of thought, authority figures began to segregate their constituents by definitions of their choice. Sick, healthy, mad, odd… such categories determined the amount of surveillance and control that needed to be employed, as a matter of “safety”. Hence, disciplinary partitioning. We note, at this point, that effective surveillance always involves visibility. The more that one can see, the more one can control.

In the panoptic mechanism, both as a structure and as the phenomenon that Foucault describes,

“…arranges spatial unities that make it possible to see constantly and recognize immediately. In short, it reverses the principle of the dungeon; or rather of its three functions – to enclose, to deprive of light and to hide – it preserves only the first and eliminates the other two.”

Let’s go back to Bentham’s ideas. The gaze of the single guard or small host of people in authority is both an actual fact and a perceived sensibility. There is a constant reminder of their presence in the guard tower itself. There is, as well, the constant threat of punishment. Inmates, then, are encouraged to behave at all times.

Such an analogy is applicable to a wide variety of situations. The preservation of law and order in contemporary society, in fact, seems to be premised upon the idea of surveillance. A government has disciplinary mechanisms in place – like the police force, or the army – that possesses the means to “correct” undesirable behavior. A government also reserves the right to censor “delicate” information, or open the records on a subject of their choice when the need arises.

LOOKING AT THE HUNGER GAMES WITHIN THE FRAMEWORK OF THE PANOPTICON

In The Hunger Games, the primary panoptic mechanism used by President Snow was the tournament itself. Its visibility and constant reminders of its existence is exerted by mandatory televised proceedings. Panem’s government also make it a point to saturate the daily existence of its citizens with The Hunger Games by making it a huge production. State regulation on all other information lends itself well to this fantasy. The suffering of the people of the District is rendered invisible to the people of the Capital because of high levels of censorship.

It does not help, of course, that everything is carefully, methodically scripted, from what is said to what is shown on the screen. This horrific level of control is then wrapped up in the wonders that a life of excess can provide: comfortable homes with all the amenities, beautiful clothes, an abundance of great food, and the perfect, riveting narrative of the Hunger Games to underscore the might of the nation. Why discuss “hard” topics like social inequality when you can occupy yourself with the latest lifestyle trends, or gab off all day about your favorite tribute for the next Hunger Games tournament?

The Capital paints itself as a generous benefactor to “obedient” citizens of the nation. Recall how victorious tributes are “rewarded” for their participation in The Hunger Games – and how Panem’s government continues to regulate how they live the rest of their lives, without civilians in the Capital knowing, or caring. In the meantime, Districts who conform best to government control win more favor for themselves at the “small” cost of their freedom and the lives of their children for generations to come.

The reach of Panem’s propaganda machine is extended through the use of a strictly controlled network of televisions and radios. Heavy censorship, excellent timing, and clever scripting help Panem gloss over what the government is really doing. Close to no one in the Capital views the Hunger Games as a means to punish the Districts and keep everyone in line. It’s the prison structure that we described above without the label. The consequences for this prove to be horrific at the end of the trilogy, and ultimately contribute to the collapse of President Snow’s control.

The same system, as previously stated, was employed by the rebels. At several points in the narrative, the Districts manage to hack into the Capital’s network. They use these as windows of opportunity to counter the government’s propaganda with a compelling narrative of their own, built upon Katniss as the Mockingjay.

Katniss eventually gets a television crew following her around on her “exploits” throughout the Districts. The movie is especially good at showing how this crew ensures that the general public gets the kinds of shots, images, and rhetoric that they need. The dichotomy between what’s shown on screen and what’s actually happening becomes clear: Katniss is shown to supposedly fighting for the Districts but in actuality she’s spirited away from most of the conflict.

District Thirteen makes it a point to mix in a lot of propaganda with slivers of truth, both to scare the Capital and to boost morale among the rebels. Everything Katniss does is regulated, making one wonder if she escaped one media-run dictatorship only to fall into the cage of another. She chafes at this control, especially when it becomes obvious to her that Alma Coin – the president of District Thirteen – is trying to use her and the other tributes to seize power.

Once it becomes evident that her building Katniss as a living symbol was a mistake, Coin comes to view Katniss as a threat. She underestimated Katniss, thinking that she would simply conform to the panoptic systems that she was attempting to control. Attempts at punishing her also did not work, traumatizing as they ended up being. Katniss eventually rose above Coin, and took matters into her own ends at the end of the trilogy by assassinating her before the nation’s eyes.

A look at the major conflicts that have occurred between national powers in recent history will show that war is fought through propaganda just as much as it is done on the battlefield. In order to sustain a wair, one must be successful in vilifying the enemy while building up an imagined sense of nationhood and patriotism. Part and parcel of doing this means employing a system of censorship carefully selected facts toted around as “the truth”.

This is something that Collins appeared to emphasize on throughout the course of the trilogy. In fact, it may be not be so far off to say that it is something that Collins – as author and individual – is intimately familiar with.

Stay tuned for the last installment of this series!

![‘The Hunger Games’ – Spectacle, Panopticon & a Culture of Paranoia [2/3] ‘The Hunger Games’ – Spectacle, Panopticon & a Culture of Paranoia [2/3]](https://i0.wp.com/whatsageek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/screen-shot-2014-09-10-at-11-21-40-am.png?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)

![WTF Wattpad: ‘Raped and Got Pregnant By A Vampire Prince’ [Part 1] WTF Wattpad: ‘Raped and Got Pregnant By A Vampire Prince’ [Part 1]](https://i0.wp.com/whatsageek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/raped-and-got-pregnant-by-a-vampire-prince-1.jpg?resize=390%2C205&ssl=1)

![WTF Wattpad: ‘Claimed by my Bully’ [1/4] WTF Wattpad: ‘Claimed by my Bully’ [1/4]](https://i0.wp.com/whatsageek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/WTF-Wattpad.jpg?resize=390%2C205&ssl=1)