‘The Hunger Games’ – Spectacle, Panopticon & a Culture of Paranoia [3/3]

Here’s the third and last installment of a series of posts on The Hunger Games trilogy by Suzanne Collins. You can find the first post over here, and the second post over here.

Please note that all of the articles collected under this series will contain spoilers for The Hunger Games trilogy. You’ve been warned!

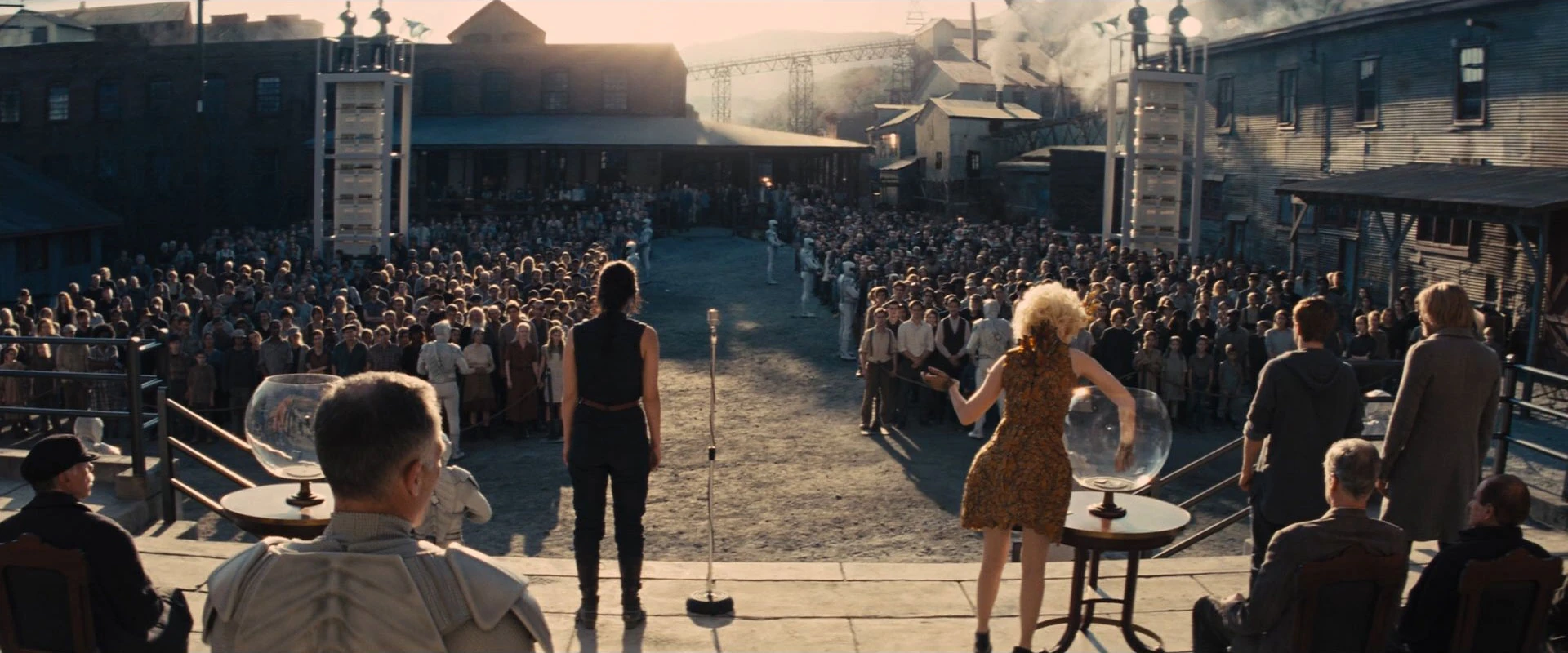

In the previous installment, we went a bit into the Michel Foucault’s conception of the Panopticon. We then used that framework to analyze media control and propaganda within the fictional world of Panem. We’re going to conclude our discussion on The Hunger Games by talking about Suzanne Collins’ reasons for writing the trilogy, the war on terror, coverage of global conflict, and young adult fiction.

ECHOES OF THE WAR ON TERROR

In a 2008 interview, Suzanne Collins was asked what inspired her to write The Hunger Games. She gave an incredibly intriguing answer.

“One night, I was lying in bed, and I was channel surfing between reality TV programs and actual war coverage. On one channel, there’s a group of young people competing for I don’t even know; and on the next, there’s a group of young people fighting in an actual war. I was really tired, and the lines between these stories started to blur in a very unsettling way. That’s the moment when Katniss’ story came to me.”

Collins later elaborated upon her childhood experience of the Vietnam War from the home front. She spotted war footage on television in spite of her mother’s efforts to protect her from the reality of it. She knew, as well, that her father was on the frontlines – a heavy fact that contend with for anyone, especially someone very young.

It is interesting, in a sense, that she cited both the Vietnam War and the conflict in Iraq: two fights that are, to date, among the most sensationalized and propaganda-ridden campaigns ever spearheaded by the United States of America. In both cases, the heads of state claimed that it was their “democratic duty” to send soldiers off to these foreign countries in order to keep the so-called war from reaching American shores.

Of course, unlike the Vietnamese War, the American audience had a much more real, tangible experience of the power of the enemy because of the bombing of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. The civilian deaths and physical damage caused by the act became the focal point of the Bush Administration. It became the forefront of the discussions, and the most popular defense of their decision to send American troops to the Middle East. Several other countries also responded favorably to America’s battle cry, both because of diplomatic ties, and because the deaths during 9/11 were not purely American.

The years that followed showed increasing disfavor over the decision to fight. Perhaps this lack of support was bolstered by counter-propaganda that made apt use of military figures and subtle jabs in works of fiction. There were, as well, “personal accounts” both by soldiers who had fought in the Middle East and the families they had been forced to leave behind. The crash of America’s economy only aggravated the situation. Many Americans questioned if their country could continue to afford sending troops overseas to fight to “liberate” a foreign nation when America itself had its own “problems” to deal with. In fact, it can be said with some authority that Barrack Obama’s victory in 2009 was sealed by the fact that he was vehemently opposed to the war on terror and had promised the American people that he would “bring their boys home”.

Another thing that may have strengthened general sentiments on the matter is the fact that a good number of articles on America’s “mistakes” regarding the war on terror have been published, so much so that Wikipedia has a pretty extensive entry on the criticism that draws from a notably large number of sources. Nevertheless, while the criticism is technically perceivable, naysayers and critics alike were always on the periphery of a larger mechanism build around positive propaganda regarding the war.

Let’s note, as well, that the war on terror has taken on a real religious tone, often equated to a fight between “good Christians” and “heathen Islam”. Anti-Islamic sentiments haven risen to an all-time high, as did an increasing sense of paranoia towards “outsiders”. A constant, visible manifestation of this paranoia can be seen in the revision of international airport security guidelines, with American airports being the strictest of them all. It can also be perceived in what the American people concern themselves with during national events, such as elections.

While support for the war on terror has dwindled, the effects that it has had on the psyche of the American people can still be felt. It determines their regular dealings with foreigners and the rhetoric that the general masses use when they speak of Islam. It also manifests itself in national and federal policy, and in contemporary fiction.

It is one thing to be in the “proper” position to criticize a war by merit of one’s social position or age. What becomes of a generation of children who were either born during the height of the war on terrorism or were too young to truly understand what was happening? “Young adults” – the perceived audience of The Hunger Games – fall precisely within this category. What does the presence of the trilogy within the genre indicate for young adult fiction as a whole, and for a more general body of readers?

DYSTOPIA, “DARKER” THEMES & YOUNG ADULT FICTION

The matter of defining precisely what we mean when we say “young adult fiction” is a constant debate. According to Dinah Stevenson, however, a common editorial consensus is that young adult books are “books for readers who are between childhood and adulthood”. Demographics based on age also vary greatly, but the safest range that a scholar can work with would be that the target audience of young adult fiction is meant to be boys and girls between the age of twelve and eighteen. More than a few scholars believe that young adult fiction is simply a subgenre of children’s literature.

Defining young adult fiction isn’t the only issue at hand. There is a lack of critical material due to the relative “youth” of young adult fiction as a category. There is also the “supreme reign” of popularity and trending patterns evident within the category and the swiftness in which works end up being seen as “dated”. Furthermore, young adult fiction greatly suffers from issues of censorship. In her essay “Young Adult Fiction Evades Theorists”, Caroline Hunt noted that

Many books that speak directly to the adolescent experience use language that some adults do not like, mention experiences (especially sexual experiences) that make some adults uncomfortable, and examine the possibility, at least, of serious challenges to authority. …children’s books do not always involve obvious taboos, but the YA ones generally do. Nor are these taboos limited to “New Realism” titles: increasingly, parents object to fantasies as well.

She goes on to note that as a result, scholars of young adult fiction have the tendency to devote most of their time to defending the works they study rather than viewing them with a critical eye and a proper theoretical framework. This just aggravates the issue of a lack of scholarship in the field.

Series like The Hunger Games are no exception. They often come under fire for having unnecessarily dark themes that are viewed with suspicions and fear by older generations of readers. In her article “Darkness Too Visible”, Meghan Cox Gurdon neatly sums up the reaction that Hunt described in far less critical terms:

“How dark is contemporary fiction for teens? Darker than when you were a child, my dear: So dark that kidnapping and pederasty and incest and brutal beatings are now just a part of the run of things in novels directed, broadly speaking, at children from the ages of 12 to 18. Pathologies that went undescribed [sic] in print 40 years ago, that were still only sparingly outlined a generation ago, are now spelled out in stomach-clenching detail. Profanity that would get a song or movie branded with a parental warning is, in young-adult novels, so commonplace that most reviewers do not even remark upon it. …a careless young reader – or one who seeks out depravity – will find himself surrounded by images not of joy or beauty but of damage, brutality and losses of the most horrendous kinds.”

Any long time reader of young adult fiction or science fiction in general will know that Gurdon is not quite accurate in assuming that the genre has been all sweetness and light only until recently. Nevertheless, her statement does capture the sort of reaction that “less favorable” works of young adult fiction can espouse in an audience. A good number of critics, of course, responded, and perhaps one of the reactions that best explained why works like The Hunger Games are well-received by their target audience.

In her article “Young-Adult Fiction Takes a Dark Turn”, Katie Roiphe she points out that new disaster fiction makes their readers “feel less alone”. She also notes how teenagers identify with their characters in spite of the fact that the fictional experiences are well outside of the range of a “normal” daily life. Furthermore,

“…the extreme and unsettling situations chronicled in these books are, for many teenagers, accurate and realistic depictions of their inner lives. Your whole family may not have died in a car wreck, but it sometimes feels like they have. Everyone in the school cafeteria may not be plotting to kill you with bows and arrows, or knives, or mutant killer insects, but it feels like they are. In the theater of adolescence, with all the sturm and drang of separating from parents, with the total stress of just having to be yourself in the hallway at school, perhaps these books feel, at times, like a true and reasonable representation of daily life.”

Another way of looking at things is to assume that the genre that The Hunger Games belongs to – dystopic science fiction for a “young” audience – is, in fact, a didactic tool. According to Kay Sambell, author of “Carnivalizing the Future: A New Approach to Theorizing Childhood and Adult Science Fiction for Young Readers”, dystopic science fiction shows the future as “a terrifying nightmare that child readers must strive to avoid at all costs”. Children’s dystopias “seek to violently explode blind confidence in the myth that science and technology will bring about human “progress”. They do this by portraying an application of science in worst-case scenarios showing how it can be used to impose horrific, dehumanizing conditions upon an entire body of people.

Dystopic fiction has always played a role in foreground social and political questions regarding the direction of the social context that they have risen from. Dystopic fiction for a younger audience may be doubly didactic, written for the specific purpose of showing children and teenagers alike how bad it can get, and why they need to avoid it.

Is Hunger Games, therefore, an attempt at critiquing American society and exposing a culture of paranoia? Collins herself seems to have an answer:

“…But there is so much programming, and I worry that we’re all getting a little desensitized to the images on our televisions. If you’re watching a sitcom, that’s fine. But if there’s a real-life tragedy unfolding, you should not be thinking of yourself as an audience member. Because those are real people on the screen, and they’re not going away when the commercials start to roll.”

As such, beyond its ability to connect to its audience through an “accurate portrayal” of a teenager’s inner world, perhaps it would be important to view a story like The Hunger Games as “relatable” social critique.

CONCLUSION

Fourteen years have passed since the 9/11 Tragedy. Osama Bin Laden, one of the principle figures behind the Al-Qaeda, has been killed, but our news and social media feeds are now flooded by rhetoric and articles on ISIS. On top of wrestling with issues like gun control and the economic recession. the United States is also contending with a violent resurgence of racism and the refugee crisis.

The global community, in the meantime, has plenty of its own concerns. The Philippines, for one, finds itself looking on with horror as China claims ownership over islands that should be officially recognized by the United Nations as a part of the island nation’s territory. Leaders of European countries, for another, are engaged in heated debates regarding the “proper” response to refugees flowing into the continent from ISIS-controlled territories. Finally, the global Islamic community continues to be besieged by racism, suspicion, and religious intolerance, aggravated by extremist groups that claim to be doing the Prophet’s work.

Backdropping all of this is the reality that we have a new generation of young readers to contend with. The entirety of their identity – their values, their concerns and their tastes – have been, in some form or another, shaped by the war on terror. They are also a generation of readers who was born into the Age of Information, and plenty has already been said on the potential dangers of using the Internet as a media outlet. As things stand, the number of young men and women from developed nations that that run away in order to join ISIS is a major cause for concern. There is, as well, the potential problem of raising generations of citizens who have been desensitized to conflict.

It is easy to react to the violence and destruction that fills the pages of The Hunger Games. We can mourn the so-called death of morality within the young adult fiction genre, and fear that reading such “dark work” will warp adolescent minds. A more critical approach, however, would be to ask why such narratives are becoming increasingly popular. We need to make an attempt at understanding what they may be trying to say about today’s society.

![‘The Hunger Games’ – Spectacle, Panopticon & a Culture of Paranoia [3/3] ‘The Hunger Games’ – Spectacle, Panopticon & a Culture of Paranoia [3/3]](https://i0.wp.com/whatsageek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/vv-mjp1.png?resize=800%2C445&ssl=1)

![WTF Wattpad: ‘Raped and Got Pregnant By A Vampire Prince’ [Part 2] WTF Wattpad: ‘Raped and Got Pregnant By A Vampire Prince’ [Part 2]](https://i0.wp.com/whatsageek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/raped-and-got-pregnant-by-a-vampire-prince-1.jpg?resize=390%2C205&ssl=1)

![‘The Hunger Games’ – Spectacle, Panopticon & a Culture of Paranoia [2/3] ‘The Hunger Games’ – Spectacle, Panopticon & a Culture of Paranoia [2/3]](https://i0.wp.com/whatsageek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/screen-shot-2014-09-10-at-11-21-40-am.png?resize=390%2C205&ssl=1)